Palaeontologists from the University of Warsaw and Polish Geological Institute – National Geological Institute have described the remains of a Jurassic ray-finned fish from the pycnodont group. It is a “cousin” of modern parrotfishes. The research was led by Dr Daniel Tyborowski, a palaeontologist from the Faculty of Geology at the University of Warsaw. The results of the research were described in the scientific journal “Geological Quarterly”.

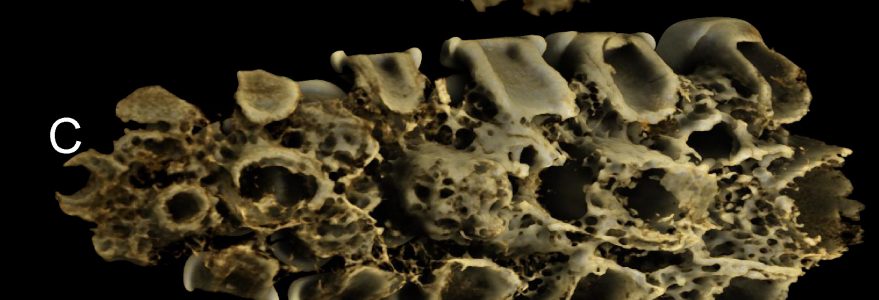

The scientists examined the remarkably well-preserved toothed upper jaw of a predatory fish from the Jurassic period (about 148 million years ago). The find comes from the Owady-Brzezinki quarry (north-western fringe of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains). At the end of the Jurassic, the area was an archipelago of tropical islands in the middle of a shallow sea. Lagoons were formed between the islets, in which a rich ichthyofauna developed.

Research on Pycnodontiformes from Poland involved: Dr Daniel Tyborowski – a palaeontologist from the Faculty of Geology at the University of Warsaw, specialising in the evolution of dentition and feeding habits of marine vertebrates from the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras, and Weronika Wierny – an expert in reconstructing fossil environments from the Polish Geological Institute – National Research Institute in Warsaw.

“Cousin” of the parrotfish

The jaw that was discovered belonged to a ray-finned fish of the pycnodont group (Pycnodontiformes), an extinct evolutionary branch of reef fish that resembled today’s parrotfish in shape and lifestyle. This group appeared at the beginning of the dinosaur era in the Triassic period (240 million years ago) and became extinct at the end of the Eocene, about 35 million years ago.

“It was at the end of the Jurassic (between 160 and 145 million years ago) that the fish reached the peak of their biodiversity, when they were an important component of lagoon and reef marine ecosystems,” says Dr Daniel Tyborowski from the UW’s Faculty of Geology.

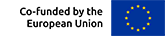

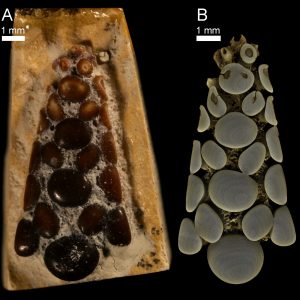

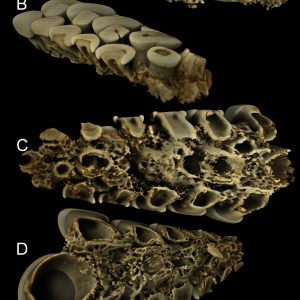

The researchers describe that a distinctive feature of Pycnodontiformes was their teeth.

“They were shaped like flat and wide cusps, somewhat resembling grains of gravel. This structure of the dentition was an adaptation for feeding on hard prey,” adds Dr Tyborowski.

The diet of pycnodonts included bivalves, snails, sea urchins, brachiopods, crustaceans and even other fish. The flat and extremely resistant teeth acted as querns that crushed and ground even the toughest prey into a fine mush. These fish were aided in devouring tough prey by their elaborate jaws, to which powerful muscles were attached. The flat teeth and strong jawbones meant that even the most armoured animals had to be on their guard against pycnodonts.

Polish researchers performed microtomographic analyses of the dentition of the upper jaw of a pycnodont from the Świętokrzyskie Mountains. The results showed that the teeth from the posterior part of the upper jaw were characterised by significantly higher tissue density than those from the anterior part of the mouth. This means that the fish used mainly the teeth located deep in the mouth to crush its prey.

“This finding is surprising because in pycnodonts known from Germany, analogous radiological studies have shown an increased density of tooth-building tissues from the anterior part of the lower jaw. What we have here is a reverse specialisation of the lower and upper jaw dentition. The use of the posterior teeth for crushing prey seems to make more sense as there is an increase in tooth size towards the throat in most pycnodonts. Perhaps a kind of asymmetry in the functioning of the chewing apparatus has evolved in this group of fish,” Dr Tyborowski emphasises.

The results of the study are described in the “Geological Quarterly” journal >>

Tyborowski, D., Wierny, W., 2025. Dental microtomographic evidence for functional heterodontty in the upper jaw of a Late Jurassic pycnodont actinopterygian fish, Geological Quarterly, 69, 13.