Tanystropheus is a six-meter, 230 million-year-old reptile. Its extremely long neck reached the size of half of its body. Dr Mateusz Tałanda and Adam Rytel from the UW Faculty of Biology, among other researchers, investigated the secretes of the length of the neck of the extinct reptile. Their work results are published in Royal Society Open Science.

A human, a whale, a giraffe and a mouse share one common feature – they are all mammals. Predominantly, in mammals there are seven cervical vertebrae. The number of vertebrae is essential in the growth and development of an organism. Researchers point out that the increase in the number of vertebrae leads to terminal disorders and tumours as early as in the foetal stage.

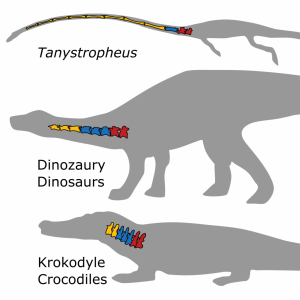

“An elongated or shortened neck in mammals means a change in the length of its cervical vertebrae rather than adding or removing any of them. It was supposed that birds and reptiles did not encounter such a constraint. For example, in swans the number of cervical vertebrae ranges between twenty-two and twenty-five while in extinct marine reptiles, such as plesiosauria, it was over seventy,” explained Dr Mateusz Tałanda from the Faculty of Biology, the University of Warsaw.

Tanystropheus and its neck

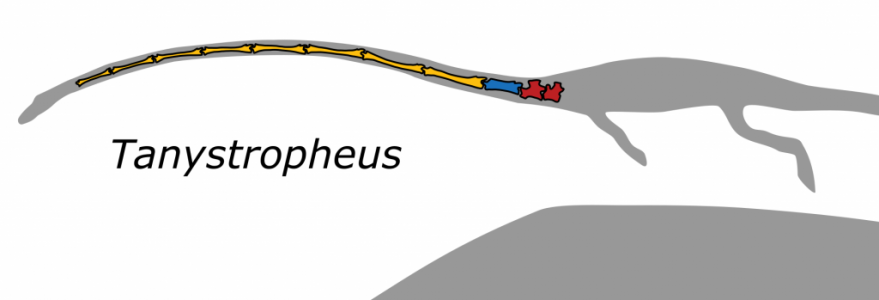

The scientists from the UW Faculty of Biology as well as other research centres investigated cervical anatomy of Tanystropheidae, an extinct family of archosauromorph reptiles, not only on the grounds of sheer morphology, but also within evolutionary and developmental aspects. The obtained results showed that the evolution of the vertebral column in these reptiles was subject to the restrictions similar to those in mammals’ necks. The researchers indicate that representatives of this species underwent an intensive evolution to adapt to various environments, i.e. land, sea, air. Nevertheless, their necks and main bodies always consisted of twenty-five vertebrae. This was true even in the case of Tanystropheus, a reptile with an extremely elongated neck. The conducted investigation also revealed that Tanystropheus, since it was not able to increase in the number of cervical vertebrae due to developmental constraints, significantly elongated the already existing vertebrae, thus reaching unusual in other species sizes.

For decades paleontologists have been attempting to explain the modularity phenomenon of the neck of Tanystropheus. “New research into the evolution and development of these reptiles allows for further comprehension of the processes responsible for such an unusual body anatomy. It is likely the result of a number of developmental constraints on the selection pressure, which, subsequently, exerted the elongated neck, similar to the neck in present giraffe,” Dr Tałanda said.